How Betrayal Almost Made Me Lose Trust

When someone betrays us, romantically or professionally, our instinct is to distrust. But the price of distrust far outweighs its benefits. Here’s why…

I’ve always thought of myself as a trusting person—both in my personal life and my work. Contracts, for me, are secondary to handshakes, and collaboration flows best when rooted in mutual trust.

But a few years ago, I had a professional experience that caused me to question my inclination to trust.

It involved a woman named Clare, a friend of a friend, whom I met and eventually agreed to collaborate with on a media project. She was smart, creative, and fun, and I looked forward to working with her. I even turned down another project in favor of that. I worked hard on my side of the project, producing a lot of video content, but when Clare edited the content, she added all kinds of special effects that I felt distorted the message. We couldn’t agree on how to proceed; so we parted ways. Before we ended things, I paid for her time and the video editor’s time. I also covered the cancellation fee for the hosting site, even if the sum made me raise an eyebrow. That was when things got weird.

To cut a long story short, I found out that Clare had not been paying the editor nearly as much as she had told me. And, worse, there had been no cancellation fee. In fact, we had been paid an advance, which she’d never shared with me. Upset, shocked, and offended by those financial betrayals, I decided to confront her–to no avail. She was evasive and confusing, and I eventually decided to drop it and move on.

When I stopped to think about it, I realized it was not the lost money that bothered me most. It was the residue from the experience–the betrayal and shattering of trust. We all have stories like this, in which someone betrays our trust. I guess that most people share my first instinctive reaction: to review how we tend to trust people and how we might be susceptible to future betrayals.

As in the cases of many betrayed lovers, one betrayal is sufficient to make the betrayed person rethink their whole view on trust. They stop trusting their lover in all kinds of ways, not just within the context of their romantic relationship but also in their partner’s capacity to make small decisions, keep promises, or even act in their best interest in unrelated matters—turning every interaction into a quiet test of loyalty that rarely feels reassuring. This newfound circle of distrust often expands to include other people and other activities. As the betrayed person decides to stop trusting, this resolution makes them feel good; distrust has given them a sense of control–and restored the sense of predictability.

Back to the story. Within the few days following Clare’s betrayal, I had indeed decided never to trust anyone again. Lawyers and contracts, I presumed, would make sure this never happened again. But then I thought that I should perhaps do a more deliberate cost-benefit analysis before implementing this approach. Making good decisions, after all, is supposed to be my profession.

Thinking about broken trust, I asked myself: What have I gained over time by placing a lot of trust, maybe too much, in everyone I work with, and what have I lost?

The losses were clear: the Clare fiasco, of course, as well as a few financial episodes and heartbreaks. But—and here is the interesting point—the advantages were not.

While the negatives of placing trust in people are obvious, the benefits tend to be elusive and somewhat hidden.

So I thought about them. I considered the trust I place in people when I start working with them, usually after I specify that I fully trust them, that I don’t need any reports from them, and that I am available should they need me. Clearly, that attitude (of trust) was yielding a lot of benefits. Not only could I be involved in many more projects with higher efficiency, but the people I collaborated with felt empowered. We were having more fun, we did not drown under bureaucratic burdens, and so on.

In light of that, I saw what would happen if I gave up on trust. I might eventually protect myself from potential betrayal, sure, but I will most certainly lose all those amazing benefits. As painful as my experience with Clare had been, it helped me realize the following: although the benefits of trust are not as apparent and easy to measure, they are substantial nonetheless, and must not be denigrated. I therefore needed to look at the betrayal as the cost of doing business and not throw the (trust)baby out with the Bathwater.

This lesson is even more applicable on a societal scale. It can be tempting, when faced with a world in which trust is an ever scarcer commodity, to withdraw it and seek ways of self-protection. Doing so, however, creates a larger ripple and reduces trust in the societal pool. When companies—or even worse, governments— do that, they damage one of the most important fabrics that bind us together. They do not recognize that withdrawing trust from a specific activity will decrease the likelihood of that particular abuse happening again at the cost of reducing overall trust, goodwill, and cooperation. The withdrawal of trust may feel good in the short term, but its long-term effect is overwhelmingly negative. Our ability to collaborate and succeed as a society relies on our ability to trust.

That is why the question is not whether we can afford to trust again; but if we can afford not to, for that is the real danger.

Irrationally yours,

Dan Ariely

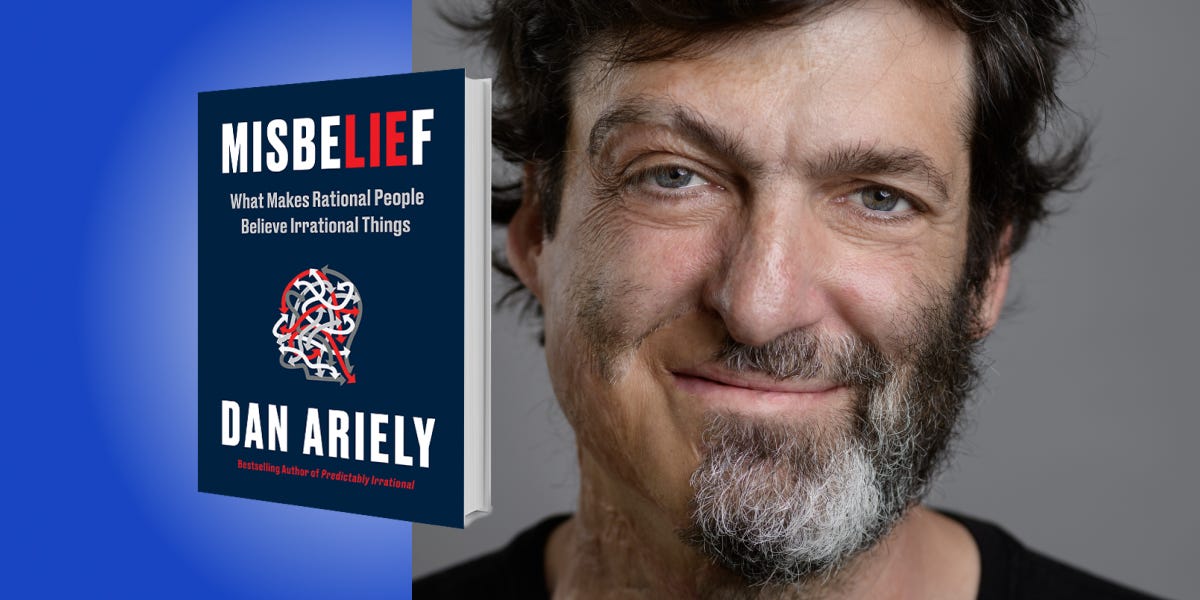

P.S. This story is adapted from an excerpt in Misbelief.